During the ‘Global Financial Crisis’ (GFC), which most of us with connections to the honorable game would have suffered, I was asked how golf courses were being affected. None too good I fancied and was able to observe with certainty that the last thing on the minds of developers and corporations was the prospect of building another golf course. – Michael Wolveridge

Golf course design firms worldwide struggled to find work and most had rationalised their practice. Golf clubs were finding the going tough, some even closing their doors and selling up as running costs reached prohibitive proportions and members withdrew their patronage, no longer willing to pay skyrocketing subscriptions and fees. Inspired through necessity, a desire was there once again to relocate from suburbia to further afield and more affordable countryside.

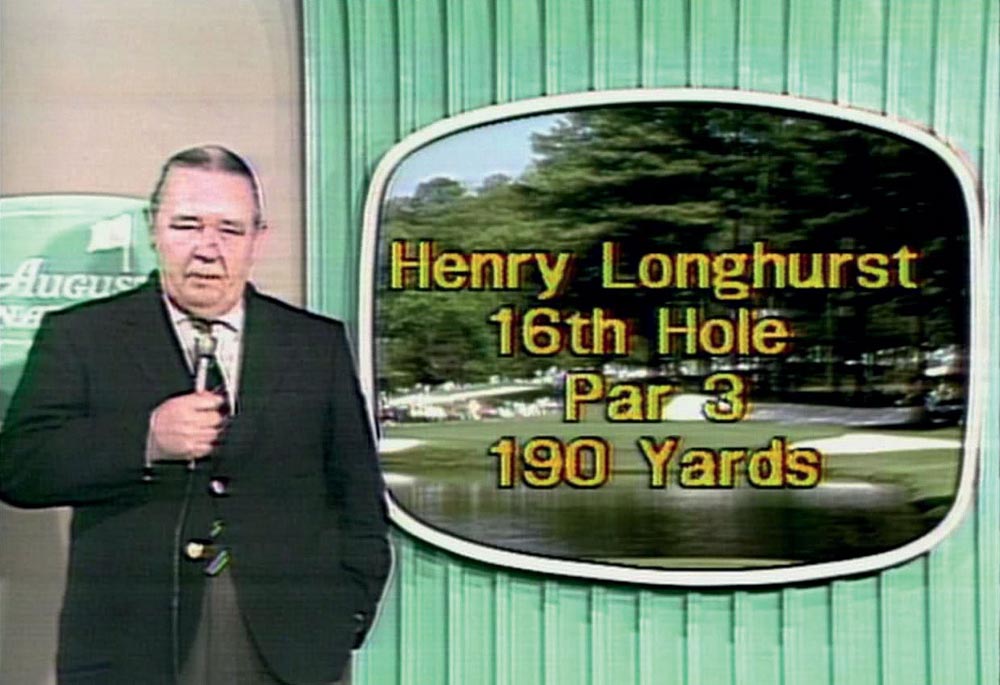

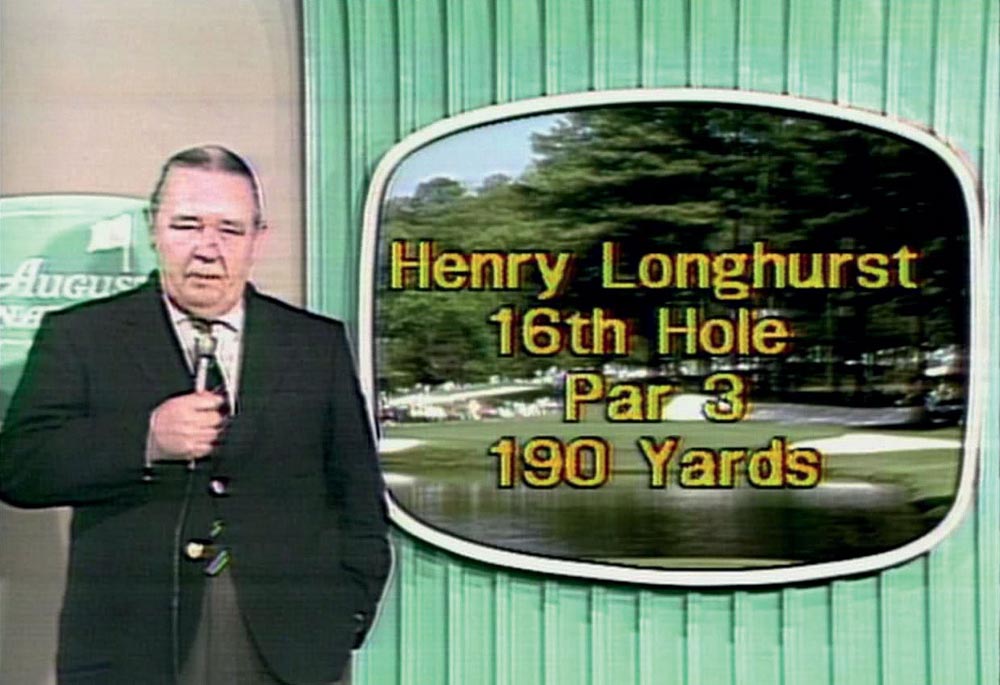

What would the inimitable Henry Longhurst have made of golf’s ‘Hard Times’? : What would Longhurst make of it? – Golf and the GFC – Issue 14 – Michael Wolveridge

‘Hard Times’ were the words that sprang to mind as I conjured up Dickens’ vivid portrayal of social life and deprivation in Victorian England. Thinking this might be a trifle harsh, I was reminded of a title with an opposite ring: My Life and Soft Times– an agreeable chronicle of a part of his life put together by the inimitable Henry Longhurst in 1971. What would he have made of current times, as he sat at his desk on a Saturday morning in deepest Sussex, in one of those twin windmills ‘Jack and Jill’, pondering his regular piece for The Sunday Timesover the first half of a bottle of Pol Roger. “With admirable discipline if I might say”, we were informed by the great man himself, “for it was not until the piece was safely telephoned through to London that the second half was broached”!

BRILLIANT DESTINATION: A sort of minimalism has quietly taken place inspired by those early days where the game invented itself alongside sandy shores, like Pacific Dunes in Oregon – What would Longhurst make of it? – Golf and the GFC – Issue 14 – Michael Wolveridge

For a good many years I came to know Henry well enough not to miss this weekly treat of topical golfing chat and to even enter a cheeky dialogue on occasion. Golf for him was, to take his words “a lifelong passport to earning a crust”, through his famous Sunday morning column which he penned for 40 years, several books and for his commentary on BBC television, broadcasting some worthy golfing event. For quite some time in his later life he occupied the prime spot at the action-packed 16th hole at Augusta for American television in their annual broadcast of The Masters, whence he would journey the first week in April “to earn a few dishonest dollars”. None of the verbal diarrhoea from Longhurst of the sort we are forced to suffer these days when the hero of the day lines up and misses a short putt. Rather, “oh dear!” followed by excruciating silence was all we got from Henry, as we made our way to the kitchen to put the kettle on, pondering – mercifully without help – the sort of anguish he who just missed the tiddler was suffering. Television rediscovered golf courtesy of Henry… or did it discover him? They certainly seemed a perfect fit as we settled in to fireside encounters with the professional game before his comforting commentary which contributed so much to popularise golf in those early days, played in places one hardly dreamed of as being likely to embrace the Royal and Ancient pastime. It was the 1970s – and golf was on the march!

Those years ago, and far from hard times, golf practically galloped around the world. With golf course architects doing their level best to keep up with demand they blazed a trail to all kinds of exotic and wondrous destinations with their new courses. As an indication and over a 30-year period commencing in the late 1960s, our firm managed to design some 80 projects in South East Asia and Japan alone. Perhaps they were our halcyon days: a smallish group of established international design firms opening up golf to thousands of new golfers eager to embrace their marvelous new game and develop their own passion and opportunity to share their homelands with the greater golfing world. Almost each one deserved of a little travelogue of its own, so beautiful and unlikely were so many of the locations.

The Americans led the great golfing boom. It commenced in the early ’60s with huge thanks to Arnold Palmer, President Dwight D Eisenhower, with television coverage led by Mark McCormack and of course the great and noble game itself. All combined brilliantly to make golf the most popular outdoor game on the planet. Golf was to open a doorway to an agreeable lifestyle for tens of thousands of Americans, followed in short order by Japanese, Europeans and Asians.

More recently, of course, it has infiltrated China. Millions of people waiting to discover golf, as a second golden age of golf course building followed the great original burst in the 1920s with a more recent generation of courses in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.

Sadly in my opinion, we couldn’t leave a perfectly splendid game alone – the manufacturers of golfing equipment, with little or no interference from those appointed guardians of the game, the R & A and the USGA, found a need to “improve” it, and so they set about their agenda by senselessly creating golf balls and golf clubs which reduced classic old courses to virtual pitch-and-putt tracks. With current equipment, truck drivers can crunch a ball 270 yards without a great deal of skill being required and top playing professionals are averaging their tee shots a massive 300 yards (and amazingly straight), courtesy of clever configurations of dimples on the golf ball. Of some necessity therefore, new golf courses grew bigger and so too did their budgets. (It just “growed and growed” as Alice might have said.)

What would the inimitable Henry Longhurst have made of golf’s ‘Hard Times’? – What would Longhurst make of it? – Golf and the GFC – Issue 14 – Michael Wolveridge

The first cracks appeared during the ’90s after oil prices had already rose substantially and affordable water supply had diminished critically. Golf clubs everywhere began to reel under the high costs of caring for their extravagant new courses, as memberships declined and corporate money tightened. Up until this point, both public and private club golfers had become accustomed to high standards of maintenance; indeed such facilities were often in open competition with one another, influenced no doubt by the enormous popularity of the televised tournaments which showcased immaculately groomed courses every week, particularly those on the PGA Tours. Golf courses were presented greener and greener and fairways were mowed shorter and shorter, creating a practice of intensive maintenance that should not and could not continue. And it did not. The mighty bubble burst.

To a larger extent, golf in Britain, Europe and in Australia and New Zealand is not played on turf quite so artificially induced as the turf on many courses in the United States. Standards are set at a more modest level so when the ‘crunch’ arrived – and it certainly did – there was a more ready acceptance of the inevitability for reduced maintenance standards. Among notable exceptions were those exotic golf courses in South East Asia due, of course, to lower labour costs and prosperous local economies.

This phenomenon inspired a few knowledgeable course architects and brave developers to set about creating their new golf courses in a more simple style – a style more familiar a hundred years ago, long before bulldozers and for that matter, before the curse of controlling councils and local government departments, demonstrating their complete ignorance of the benefits to the community of well-made golf courses, started saying ‘No!’ to every application to bring public golf beside the seaside… where it traditionally belongs. And so it followed at a few brilliant destinations, like

Bandon Dunes on the Oregon coast and Cape Schanck and Barnbougle Dunes in Australia, in Scotland at Macrihanish and at St Andrews, the Home of Golf where they continue to add more seaside courses, a sort of minimalism has quietly taken place inspired by those early days where the game invented itself alongside sandy shores.

Not that great golf cannot be played on suitable inland sites, as the success of splendid new golfing developments among the prairies and wild dunes of Nebraska will attest in inspiring a spate of golf courses resembling coastal links embodying, as they do, all the benefits of building on well-drained sandy soil, fully exposed to the elements and sensitively designed with the particular lessons of the traditional game in mind. In embracing a minimalist approach, such courses require less water and less power and as a consequence, less intensive maintenance.

NATURAL SITE: The Old

Course at St Andrews. – What would Longhurst make of it? – Golf and the GFC – Issue 14 – Michael Wolveridge

This is not a complete turn-about by any means, as without the right sort of land it cannot take place… but it may be a beginning (or is it back to the beginning) of a more healthy state of golfing affairs where recognition of affordable public golf can prosper, with golf courses still providing an exacting though pleasurable challenge.

Clubhouses too can become a big part of easing annual running and maintenance costs by abandoning all concepts of elaborate building. New clubhouses may better be designed if their raison d’etre is to provide a golfing public with little more than a haven from the elements and a place to change; a simple, comfortable building serving simple fare and offering a facility where golfers might happily contemplate their recent joust with the weather, the quirks of links golf and the enormous joy of having just played golf in a good place.

With such a scenario finding increased popularity and making better economic sense, certain aspects of the GFC may even be seen as a blessing for the longevity and integrity of the game. “Perhaps it’s all for the best, dear” as our wise old mothers might have said. Henry Longhurst would like that – so too would the mighty Charles Dickens… they liked happy endings!